If, culturally, you thought we left “the R-word” back in the late ’90s, you’d unfortunately be wrong.

Elon Musk, President Donald Trump’s buddy-in-chief and the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, is among those who uses the slur regularly: In the past year, Musk, has used “retarded” as an insult at least a dozen times on X, the social media platform he owns and obsessively posts on.

Musk ― who’s always been something of a shit poster, even at 53 ― has directed the word at famed Danish astronaut Andreas Mogensen, actor Ben Stiller, and most recently, Timothy Snyder, a Yale history professor and authoritarianism expert who got under Musk’s skin by criticizing the Trump administration.

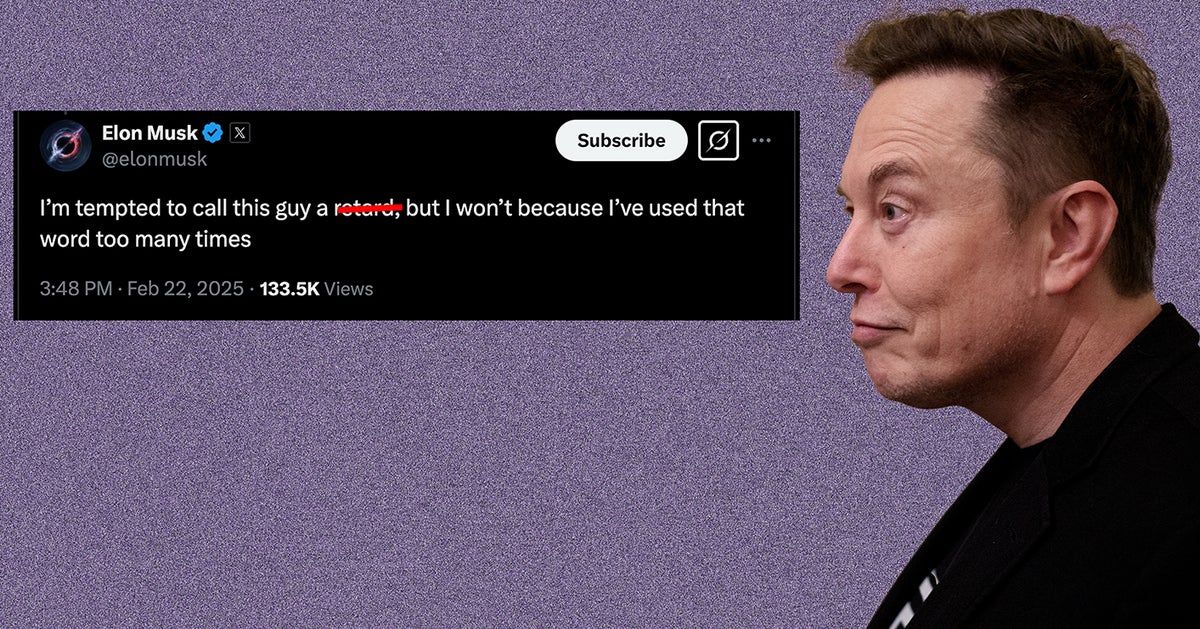

“I’m tempted to call this guy a retard but I won’t because I’ve used that word too many times,” Musk tweeted to his almost 200 million followers on Feb. 22 in response to commentary from Snyder.

You can’t lay the blame for the R-word’s comeback all at Musk’s feet ― it’s true that 4-Chan posters and wannabe edge lord comedians never stopped using the word ― but it’s undeniable that Musk’s voice has an impact. A recent study out of Montclair State University found that the use of the slur triples on X when the tech CEO tweets the word himself.

“Unfortunately the R-word is a word that is starting to come back into conversation because more people in positions of power — whether they be political leaders, business leaders, celebrities — are using it as part of their normal dialogue,” said Christy Weir, who works for the Special Olympics, the world’s largest sports organization for children and adults with intellectual disabilities.

Trump himself, of course, is not above insulting people, including those with disabilities: On the 2016 campaign trail, he mocked a reporter’s disability by performing an impression of the man. Throughout the last campaign, Trump called both President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris “mentally disabled” ― one step below the R-word in offensiveness.

In some ways, the R-word’s resurgence is a grim sign of our political moment: There’s an inherent meanness to the way the Trump administration and the president’s various cronies conduct themselves.

You can see it on the White House’s social media feeds, which include mock ASMR videos of deportations and posts mocking Selena Gomez for a tearful video she posted in response to ICE raids.

It’s aptly been called a “politics of cruelty,” and if cruelty is the name of the game, slurs like the R-word or using “gay” as a pejorative fit right in.

Andrew Harnik via Getty Images

Some couldn’t be happier about the comeback. In January, the Financial Times interviewed a number of finance bros who were glad that Trump won and that “woke” lost the election, if only because they figured it meant they’d no longer have to self-censor their language around women, minorities and disabled people.

“I feel liberated,” one Wall Street banker told the paper. “We can say ‘retard’ and ‘pussy’ without the fear of getting cancelled … it’s a new dawn.”

That’s exactly the kind of thinking that worries disability advocates like Nila Morton. Hearing Musk or Gen Z politico bro podcasters casually slip a “stop acting so retarded” into conversation makes the word more palatable, emboldening others to use it in their everyday lives.

“They’ve tested the boundaries of what they can say and do, and many people who once hesitated to use offensive language now feel encouraged to push those limits as well,” said Morton, a graduate student at the School of Social Work at Howard University.

As someone with a physical disability who uses a wheelchair, Morton has experienced ableism and the sting of being called the R-word. She doesn’t have any cognitive disabilities but has seen firsthand how painful and dehumanizing it can be for those who do to hear the word. Worse, sometimes those with such disabilities internalize the negative messages.

“Even if someone claims they aren’t referring to disabled people when they

use the slur, the underlying message remains the same: that people with

disabilities, especially those with cognitive disabilities, are less valuable,” Morton said.

“We’re not just permitting offensive speech ― we’re potentially undermining the foundation of respect upon which disability rights depend.”

– Katy Neas, CEO of The Arc

What makes the R-word’s return most depressing for disability advocates is that for the last few decades, its use was finally dying out: A decade ago, high schoolers ― historically frequent users of the word ― started campaigns to nix it from their vocabulary. They wore “Spread the Word to End the Word” wristbands and hung educational banners and flyers in their schools suggesting alternative words to use.

Now, though, even pop culture is normalizing it again, said Katy Neas, CEO of The Arc, a national disability rights advocacy group. Shows like Max’s “Euphoria” use it and introduce it to younger viewers who are mostly disconnected from the hard-fought battles to eliminate this language. (“Euphoria” may not be the most realistic teen drama, but it does tend to get the language right: Teens and adults are using the word again.)

“This isn’t an isolated trend [with Musk] — it’s part of a broader cultural shift that’s concerning for disability advocates,” Neas told HuffPost. “When we allow this slur to make a comeback, we’re not just permitting offensive speech ― we’re potentially undermining the foundation of respect upon which disability rights depend.”

John Parra via Getty Images

Why does the R-word have such sticking power?

The story of the R-word shows how our country’s relationship with disability rights has steadily evolved, Neas said.

Like the words “idiot” and “moron,” “retarded” started out as a clinical term for people with intellectual disorders. During the eugenics movement ― a time in the early 20th century when people with disabilities were forced into sterilization programs and institutionalized ― the term “mental retardation” was used to diagnose the “feeble-minded.”

It was eventually phased out of medical circles, but not before being adopted into mainstream culture as a generalized insult: “You’re so retarded.”

It remained a crass conversational fixture for some until around the late 1990s, Neas said, thanks to the self-advocacy work of people in disability communities. “We saw a real turning point in the 1990s and 2000s when people with intellectual disabilities started saying, ‘This language hurts us,’” she explained.

In 2003, President George W. Bush renamed the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation to the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities ― a move with bipartisan support that underlined how phasing the word out is ultimately about basic human dignity, Neas said.

Then came a milestone moment in 2010, when President Obama signed Rosa’s Law — named after a young girl with Down syndrome — which officially replaced that outdated R-word with “intellectual disability” in all federal language. A number of states did the same.

“It wasn’t just doctors or politicians deciding what was best, either — the push came from the community itself,” Neas said.

SAUL LOEB via Getty Images

But now that progress seems threatened, Neas said, not just because of language trends, but because the disability community is facing serious policy challenges with Trump in office.

“There are proposals for major cuts to Medicaid, which is absolutely essential for many people with intellectual disabilities, and threats to Section 504 protections,” she said. “It’s like we’re coming full circle as we’re seeing this troubling backslide in both language and rights.”

Neas thinks the R-word ― and the tendency to short-shrift the disability community ― persists largely because of a troubling societal blind spot. Unlike many other marginalized groups who’ve gained visibility in mainstream culture, people with intellectual disabilities remain incredibly isolated — they’re often segregated in schools, workplaces and community spaces. When someone is out of sight, they’re out of mind.

“It creates a dangerous disconnect: When people don’t have meaningful relationships with individuals with intellectual disabilities, using this slur feels abstract — like there’s no real person being hurt,” she said.

“The very isolation that keeps people with intellectual disabilities out of mainstream spaces allows this harmful language to continue without apparent consequences,” she added.

Here’s how we can encourage people to ditch the word again.

Sometimes, all it takes to get someone to curb their use of the slur is just to remind them that it’s still insensitive and, frankly, weird to use in conversation.

Morton pointed to how she and other disabled people on social media pointed out to rapper GloRilla that her use of the R-word wasn’t OK when she released a track in 2024 that included it.

“Some other Black disabled advocates and I made a post on Twitter, tagging GloRilla, to educate her on why the word is offensive and suggest alternative ways to express her message,” Morton said.

And instead of taking insult at being called out, GloRilla listened and replaced the word with “naughty,” which Morton thought was totally brilliant: “I’ve been playing that song ever since,” she said proudly.

Use of the R-word is still sometimes a generational thing, too. Cynthia Kreuz-Uhr, the associate director of community engagement at The Arc’s chapter in San Francisco, pointed to how she and her young daughter gently persuaded her father, a minister and psychotherapist, to retire the R-word back in the early 2000s.

“My daughter was shocked but simply said, ‘Grampy, you can’t say that word!’ My father was annoyed and said, ‘I didn’t mean it as an insult, I meant it as a diagnosis — that man’s development is delayed,’” she recalled.

As someone who works with people with developmental disabilities, Kreuz-Uhr seized the opportunity to explain to both generations how the word has evolved over time.

Instead of shaming people who use outdated, offensive language, she thinks we should invite them to support the disability justice community in their language and in other ways.

Get Our Lifestyle Coverage Ad-Free

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

“Maybe you encourage them to vote to support services for people with disabilities, or speaking directly to them instead of to the non-disabled people they may be with, or hiring qualified people with disabilities,” she said.

When trying to encourage someone to be better with language or behavior, Kreuz-Uhr’s advice said she keeps it pretty simple: “I try to follow the saying, ‘Don’t call people out. Call people in.’”

Leave a Reply