Members of the Bonus Army stage a massive protest on the steps of the US Capitol.

This story first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

When the promises politicians made went unkept, when they were left without any reasonable alternatives, American veterans took to the streets by the thousands, forced to become their own advocates.

The year was 1932, and the men who’d served in World War I were demanding the bonus pay they’d been promised for their years fighting in Europe. Calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or the “Bonus Army,” veterans hitchhiked and rode freight train boxcars from all over the country to get to Washington, DC. They protested for months, and the entire nation took notice.

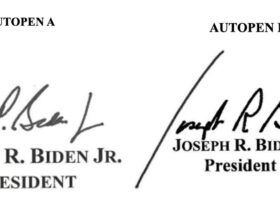

In 2025, a new Bonus Army has assembled and plans to rally in Washington on June 6 to protest the administration’s cuts to Veterans Affairs and federal employment, where veterans and their families comprise 30 percent of the workforce.

“The federal workforce is one of the only places in the entire country that truly takes into account the merit of military service, and [the cuts are] something that really pisses me off,” said Will Attig, a protest co-organizer and executive director of the Union Veterans Council, which advocates for veterans jobs and a robust VA.

Now “veterans that serve their country are being called the worst type of names and are being told that they’re DEI hires, being told that their jobs are handouts, that they’re lazy bums,” he said. “We can all agree, veterans need jobs. Veterans do better when they have good jobs, and taking that pathway away and then disrespecting the thousands, the tens of thousands of veterans that play those roles” is enraging.

The new efforts bear the name and the legacy of thousands of American soldiers who took to the streets almost a century ago, and they echo generations of veterans who have advocated for their benefits and applied their moral weight to right wrongs.

The Bonus Army protests of 1932 led to the GI Bill more than a decade later. Vietnam veterans not only protested the war in Southeast Asia, but two veterans—Sens. John McCain and John Kerry—helped lead the reconciliation efforts. Gulf War veterans steadfastly pushed to have Gulf War syndrome and the effects of Agent Orange recognized and VA benefits to treat it.

“All veterans were willing to give their lives in service to their country. In other words, we ‘walked the walk,’” said historian and veteran Marc Leepson. “And that gives us a good measure of credibility, if not gravitas” when advocating for certain issues.

The Birth of Military Protests

Much of modern military protest traces back to the original Bonus Army, according to James Ridgway, a veterans law scholar and lecturer at George Washington University.

Then, veterans had been promised deferred compensation for their World War I service, but it wouldn’t be paid until 1945. As the Great Depression worsened and families became desperate, veterans demanded their bonuses early. They marched from Oregon to D.C., where more than 10,000 camped on the National Mall and on the banks of the Anacostia River.

There, Marine Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler gave a rousing speech that is still quoted today.

“You have just as much right to have a lobby here as any steel corporation,” Butler said. “Take it from me, this is the greatest demonstration of Americanism we have ever had… Don’t make any mistake about it: You’ve got the sympathy of the American people. Now, don’t you lose it!”

Even so, at the order of then-President Hoover, the assembled thousands were routed from their protest site at bayonet point by a battalion of soldiers, machine gunners, cavalrymen, and tanks from the same Army they served in.

When images of the Bonus Army’s burning camp made the front pages of newspapers and theater newsreels across America, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was running against Hoover for the presidency that year, reportedly told an aide, “This will elect me.”

Roosevelt, who promised a “New Deal” that would provide relief and economic security for all Americans, including veterans, won the election that November by a landslide, securing 57% of the popular vote.

The struggles of WWI veterans served as a cautionary tale for Roosevelt, who signed the GI Bill in 1944. This historic law provided low-interest loans, trade education, and a college education to servicemen returning from World War II.

Veterans Fight for Truth and Treatment

Just a few decades later, the pendulum swung back with young soldiers returning from the Vietnam War. They were called “losers” by politicians and World War II veterans who did not have the same rates of post-traumatic stress disorder as their successors.

When the Vietnam veterans began to get sick from their exposure to Agent Orange or were stricken with severe addictions to help manage their PTSD, they struggled to file claims with the Veterans Benefits Administration.

As a combat lieutenant in 1969, Bobby Muller was shot while leading a charge and was paralyzed from the waist down.

After suffering deplorable conditions in a Bronx VA hospital, Muller co-founded the Vietnam Veterans of America in 1978. The VVA advocates for veterans’ issues like combating homelessness, ensuring adequate care for disabled veterans, and assisting veterans seeking government benefits and services. Today, there are nearly 90,000 VVA members in 650 chapters across the US.

“Nobody can speak for the dead,” Muller said in a 2019 interview with Binghamton University. “But I was in a position to speak for the living that had been severely damaged.”

Veterans advocacy has not just focused on winning benefits. In the spring of 1971, a young lieutenant who’d commanded a swift boat in the Mekong Delta named John Kerry spoke to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on behalf of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. In addition to vividly retelling the findings of the Winter Soldier testimony earlier that year into war crimes committed by U.S. soldiers in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, Kerry laid bare the criminality many veterans felt embodied the United States’ involvement in the war.

“We could come back to this country, and we could be quiet, we could hold our silence, we could not tell what went on in Vietnam, but we feel because of what threatens this country … not the Reds … but the crimes which we are committing that threaten it, that we have to speak out,” Kerry testified.

Kerry, along with McCain, who was a prisoner of war in Vietnam, would later push the Clinton administration to restore diplomatic relations with that country. McCain noted that his war experience afforded him a unique position. “I knew I wasn’t taking much of a political risk by advocating for normal relations. It was hard to accuse me of bad faith, and I felt pretty safe from criticism,” he later said. In the 1990s, veterans returning from the Persian Gulf also had to fight for benefits to treat their service-related injuries.After serving as an Army cavalry scout in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991, Paul Sullivan experienced chronic respiratory infections and neurological symptoms. He met other Gulf vets in VA hospital waiting rooms. They compared notes and shared their fury at being told their conditions were “temporary” and “not related to their service.” At the time, the burden heavily fell on veterans seeking to get medical care through VA.

“Veterans trusted each other, and veterans believed each other that we were exposed to toxins and that we were sick,” Sullivan said. “Then we demanded very clear objectives from VA: Why are we sick? … How are we going to get better, and who’s going to pay?”

Gulf War veterans collaborated with Vietnam Veterans of America and the Veterans of Foreign Wars to lobby for access to care and benefits from the Veterans Administration in a battle that went on for decades, according to Sullivan, who served as executive director of the National Gulf War Resource Center.

This collaboration led to the successful passage of the Veterans Benefits Improvements Act of 1994, the Persian Gulf War Veterans Act of 1998 and subsequent laws, all of which made it easier for veterans to access the health care needed to treat service-related illnesses.

That tenacity continued as veterans and their families slept on the steps of the Capitol building in 2022 to pressure senators to pass the PACT Act, which extended benefits to those exposed to toxins during their service.

Now, veterans are using a combination of their combat experiences and subsequent inadequate treatments to lobby for expanded clinical studies of psychedelics.

“After two decades of sustained combat and a persistently high veteran suicide rate, there is growing urgency—and willingness—to pursue innovative treatments for the challenges veterans face,” says Amber Capone, co-founder of Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions. “Veterans have a remarkable ability to transcend political divides and build consensus around otherwise contentious issues.”

Texas House Rep. Mike Olcott was unconvinced about a $50 million bill to research using the psychedelic drug ibogaine to treat substance use disorders, PTSD, and other mental health conditions until he spoke with a group of people, including Amber’s husband, Marcus, a former Navy SEAL.

“As a former scientist, I said ‘I’ve got to talk to someone who’s actually been through this,’ because I was very skeptical,” Olcott said. After Marcus Capone described his own experiences, Olcott remarked, there are “really good reasons to support this bill, and I’m looking forward to voting for it.”

When the Bonus Army of 2025 arrives in the Capitol on June 6th, they will have an opportunity to use this same force multiplier of veterans’ voices. Organizers say they want to protect federal employment for veterans and military families, hold politicians accountable for cuts that harm service members and families, and stop the “weakening of the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

“I think that reminding our fellow Americans that people who choose to step forward and serve—like veterans and civil servants—they should be honored not demonized,” said Scott Cooper, a Marine pilot who served numerous tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and will join the June 6 protest. “I believe in my core that citizenship can’t be a spectator sport, so I need to participate and help, no matter how small that contribution is.”

Leave a Reply