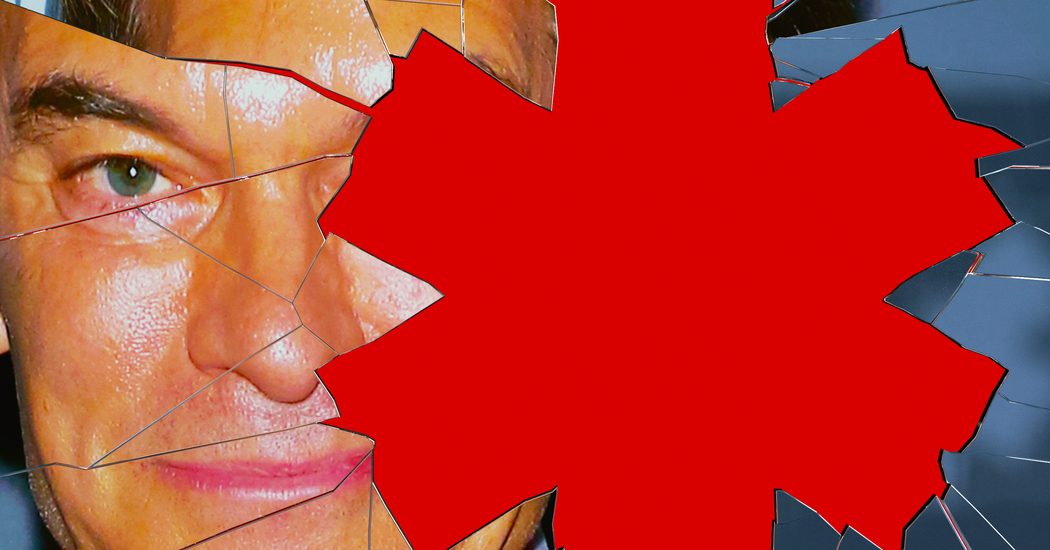

Before medical contrarianism became intrinsic to his identity, Dr. Mehmet Oz appeared motivated by curiosity rather than opportunism. Arriving at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in 1986 to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a cardiothoracic surgeon, Dr. Oz became well respected in the field. But much to the chagrin of administrators and peers, he also showed a penchant for questionable medicine.

In the mid-1990s, he invited a healer into the hospital’s cardiac operating room “to run a kind of energy, which science cannot prove exists,” through patients’ bodies. Proponents claim that kind of practice and its adjacents (think Reiki or “therapeutic touch”) improve people’s health and result in faster recovery times, less pain and better physical function for patients — despite a lack of scientific explanation for how they might do so.

“Not everything adds up,” Dr. Oz told The New Yorker in 2013. “It’s about making people more comfortable.”

This nonconformist approach endeared Dr. Oz to patients and to a public eager for a warmer approach to medicine. At the same time, it became a way to accrue decades of fame and fortune.

Those efforts have culminated in Dr. Oz’s nomination by President Trump to lead the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Senate hearings are to begin Friday. If confirmed, his appointment would be yet another signal to a new wave of charismatic health personalities that science and evidence are negotiable in the service of ambition.

In 1996, Dr. Oz helped transplant a heart for the brother of Joe Torre, then manager of the New York Yankees. It was “his first big splash of publicity,” a former colleague, Dr. Eric Rose, who led the Torre operation, said, “and he loved it.”

Dr. Oz chased the high. He guest hosted Charlie Rose’s talk show, published books and consulted on the Denzel Washington film “John Q.” Starting in 2003, Dr. Oz began hosting his own show, “Second Opinion With Dr. Oz,” on the Discovery Channel. One of his first guests was Oprah Winfrey. Soon, he was making multiple appearances on her show as a medical expert. By 2004, Ms. Winfrey was calling him “America’s doctor.”

Dr. Oz said in a 2003 interview that his approach to medicine, and by extension his show, was about making available to patients the best treatments they could afford. Noting that he had an M.B.A. in addition to a medical degree, Dr. Oz said, “I think as physicians, we are abdicating our responsibility to the society, to our community if we don’t take an active role in figuring out how to spend money.”

Dr. Oz’s answer to the money question was alternative treatments. In some cases, holistic medicine may appeal to patients as an affordable option when expensive conventional therapies failed them. But Dr. Oz’s openness to alternative medicine would gradually give way to the promotion of quackery.

“Second Opinion” lasted only one season, but in 2009, Dr. Oz returned with “The Dr. Oz Show.” By the early 2010s it was in the upper echelon of daytime TV programs. On his own show and elsewhere, he gave credence to any health fad, no matter how flimsy the science behind it. Dr. Oz touted the healing properties of hyperbaric oxygen and colloidal silver (tiny silver particles suspended in liquid), and hosted the antivaccine conspiracy theorist Joe Mercola to promote a dietary supplement.

Still, viewers ate it up — and it’s not hard to see why. In my new book, I show how media figures leverage their positions as established, trusted experts to become iconoclasts. Touting consensus wisdom makes you one of a million. But if you’re a contrarian, you immediately shrink the pool of voices competing for attention.

Dr. Oz is not a public health edge case. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. spent decades shifting further into vaccine skepticism as his stance garnered more attention; he’s parlayed that attention into a position of power as the new secretary of health of human services. The physician and health economist Dr. Jay Bhattacharya found fame through his rejection of Covid-19 mitigation policies in 2020, drawing scorn from the medical community; he’s now on track to lead the National Institutes of Health.

This reactionary strain is right at home in our electoral politics, but it marks a change from how the government’s public health policy has traditionally been decided and carried out.

In April 2012, Dr. Oz told his audience that sleeping with a sock full of heated, uncooked rice could help with insomnia; a lawsuit followed after a man taking his advice claimed he was injured. Researchers in 2014 found that only 21 percent of “Dr. Oz Show” recommendations had “believable” evidence behind them.

That same year, Dr. Oz appeared before a Senate subcommittee hearing to defend his advocacy in favor of weight-loss substances and faced pointed criticism from lawmakers. “I don’t get why you need to say this stuff, because you know it’s not true,” Senator Claire McCaskill, the Missouri Democrat, said.

In 2015, a group of doctors called on Columbia to cut ties with Dr. Oz, describing him as someone who “has manifested an egregious lack of integrity by promoting quack treatments and cures in the interest of personal financial gain.” On his show, Dr. Oz fired back, vowing not to be silenced. Two years later, a cohort of academics, writing in the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics, questioned if there should be some sort of sanction for his “inaccurate and potentially harmful” advice.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, he repeatedly appeared on Fox News to promote unverified treatments like hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, leading to intense criticism. Eventually, his show began bleeding viewers and never recovered, after which he ran an unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate from Pennsylvania.

But the reputational damage hasn’t stopped him. He already made the leap from the operating room to the TV screen; now he seems poised to enter the federal government. His fame has endeared him to Mr. Trump, and his nonconformist reputation is perfectly suited for the new health administration.

We don’t know for sure what Dr. Oz will do if confirmed as head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. He may be an effective leader. But his past is likely to prove concerning for people on Medicare and Medicaid who are counting on stable, reliable access to health care.

Dr. Oz’s confirmation could also encourage a cadre of actors to follow his path and sow more discord in what’s left of the nation’s public health structures. It’s one thing to advocate alternative methods for the benefit of your patients. It’s quite another to build a career on rejecting traditional medicine — an abdication of his responsibility as a health professional.

Leave a Reply